Panama: Dismissed Isthmus

Panama doesn’t get the respect it deserves as an adventure travel destination. It gets visitors, sure, but it’s treated more as a terminal or a bridge; somewhere to catch a connecting flight, wait for a boat, or simply pass straight through, whether by road or through the canal. Those who take the time to get to know the Panama that lies beyond Panama City and the canal, however, will discover one of the more unusual countries in the Americas and one of its last unspoiled wild regions.

If you’re on a long bike tour of Latin America, Panama is where you’ll reach two important milestones. The first is the Puente de las Americas (Bridge of the Americas), the point at which you’ll ride from North America to South America (or vice-versa, if you’re coming from the other direction) by crossing the Panama Canal. Ride on the raised sidewalk if the traffic is too heavy.

At Arraiján, you have the choice of continuing east to the Puente de las Americas or riding 10 km north to the newer Puente Centenario (Centennial Bridge). By choosing the latter route you can skip a lot of nasty city riding and instead arrive in Panama City through the lush and beautiful Camino de Cruces National Park, entering through the more-relaxed University District. You could even camp in the park for the night with no one noticing and enter the city in the calm of morning.

This route has one snag, however; bicycles aren’t allowed on the Puente Centenario (a guard immediately stopped me as I approached). I was able to hitch over the bridge, however, on the back of a pickup. I’ve cycled both routes and for me the Centenario route is worth the minor inconvenience of hitching a ride.

The other important milestone you’ll reach in Panama is the end of the first leg of the Pan-American Highway. Because it requires an out-and-back journey of several days into Darién Province, most cyclists skip it altogether and instead spend their time hanging out in Panama City waiting for a boat or flight to take them to their chosen starting point in South America. What a shame. They’re missing seeing one of the last wild frontiers in the Americas.

The mighty Pan-American Highway ends unceremoniously in Yaviza, a frontier town worth checking out for its ramshackle clap-board stilt houses and unconventional layout. The last time I was in the Darién, the pavement fizzled into mud and gravel at Santa Fé, some 80 km before Yaviza.

To really explore the Darién you should stash your bike and travel by boat. Not only is boat travel the only way to get close to the amazing nature here, it’s also the best way to meet Darién’s indigenous people. I met Emberá-Wounaan people who didn’t even speak Spanish, which led to a lot of hand gestures and smiling on both sides.

If you’ve been cycling south through Central America and your plan is to continue into South America you’ll have to decide how to pass the Darién Gap–the roadless, lawless jungle that connects Panama to Colombia. With planning, time, and personal risk, it’s technically possible cross overland using guides, but you’ll be discouraged at every step by the army, the police, the locals, the guidebooks, other travellers, your parents, and the government (both yours and Panama’s) who will cite malaria, drug gangs, kidnappings, bandits, deadly snakes, and complete lack of amenities. For most, the decision comes down to a flight or a boat. I recommend the boat.

Sailing through the San Blas Archipelago between Panama and Colombia is one of the highlights of any Latin American journey. Comprising nearly 400 mostly-uninhabited islands, Kuna Yala (as it’s also known) is home to the semi-autonomous Kuna people whom you’ll probably meet when they paddle up to your boat in dugout canoes to sell you handicrafts (especially the famous mola fabrics). The islands themselves are like something out of a dream; each a perfect ring of white, powdery sand surrounding a grove of coconut palms. You swim from one to another in bathtub-warm crystal water through schools of colourful fish. At night, the sky (unpolluted by city lights) erupts with a billion stars, and the sea, mimicking this display, explodes with its own sparkling constellations of phosphorescence. A night-time swim here counts as a psychedelic experience.

And there are other interesting adventures in Panama.

If you’re crossing from Costa Rica at Paso Canoas, consider a side trip up to Boquete. The town is a bit of an ex-pat haven (which is not necessarily a negative observation) and a good base for planning a trek up Volcán Barú (a.k.a. Volcán de Chiriquí). From the summit of this extinct volcano (the highest point in Panama) you can see both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans–an unforgettable view if you’re lucky enough to get good weather. When I did this two-day hike, I endured many hours of torrential rains in both directions, but was able to get my double-ocean view during a brief break of blue skies on the morning of the second day–absolutely worth the wet feet!

I’ve often heard cyclists dismiss Panama as uninteresting to tour. That makes sense if they simply cycled from Paso Canoas to Panama City then flew on to South America (as many do). Looking back, I agree that the best adventures I had in Panama were off the bike.

Official Name: La República de Panamá

Area: 75,517 km² (29,157 sq. mi.)

Population: 3.5 million

Capital: Panama City

National Official Language: Spanish

Other Languages: Emberá, Kuna, Ngäbere, Teribe

Currency: balboa (PAB), US dollar (USD)

Highest point: Volcán Barú 3,475 m (11,401 ft.)

Lowest point: Pacific Ocean 0 m

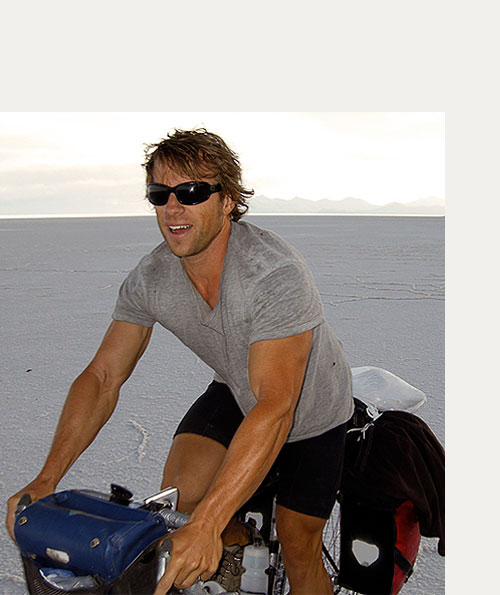

Feature image (top of page): Swimming with Emberá children, deep in Darién Province.

© El Pedalero, 2012.